Track workouts can take you places the open road can’t.

Track workouts can take you places the open road can’t.

Okay, I was wrong. For years, the whole idea of track workouts for someone like me just didn’t make any sense. It’s bad enough to be slow when I’m out on the road, alone. Why in the world would I want to prove how slow I am by running in circles on a track with people passing me every few seconds?

The answer is pretty simple: because I actually can improve by running on the track. We all can improve our running. Mind you, I have a firm grip on the limits of my potential, but I don’t think there’s any harm in reaching beyond my current abilities.

Now, I’m not talking about doing speed workouts until both my lungs turn inside out. I’m not talking about proving that I can pump my heart past its maximum rate. And I’m not talking about workouts that leave my legs in such a state that I can’t work the clutch for a week.

What I am talking about is taking advantage of a flat, measured course to work on some of the nuances of running that somehow seem to elude me when I’m out on the street or trail. Believe me, I’ve tried counting my “steps per minute” while running on the road, and it’s always disastrous. If I could do two things at once, it might work. But in my case, the number always ends up being “eleventy-something.”

On the track, however, it’s much easier. Sure, you may wander out of your lane a little, but walls or fences will keep you from straying too far. And if you shorten or lengthen your stride, it’s likely a change you intended to make, not one forced upon you by a change in the terrain.

My favorite track workout is “Yasso 800s,” named after Bart Yasso, a friend, ultramarathoner, and “Runner’s World” colleague. I like the workout because it’s a great predictor of marathon-finish time. I’m sure it’s more complicated than I make it, but for me the workout boils down to running two laps (800 meters) on the track at a sustainable, faster-than-usual pace.

The goal is to be able to run 10 800s, each in a minute-and-second time that matches your expected hour-and-minute marathon time. So, if you want to run a marathon in 4 hours and 30 minutes, you start with four or five 800-meter repeats and gradually work up to 10, running each in 4 minutes and 30 seconds.

With any interval workout, it’s important to recover between repeats. During these rest periods, I try my hardest to look as if I’m actually doing a track workout. I walk to my water bottle, wipe off my face, bend over and gasp, fiddle with my shoes, adjust my shorts, and maybe do a little half-hearted but very intense-looking stretching. Hey, I look just as good resting as any other runner.

At the track, I learn from watching the runners around me. I watch their strides and arm swings, and try to copy those that look the best. And when I’m feeling really good, I even talk to some of the faster runners.

Cooling down after a hard (my definition) track workout is one of the most pleasant running experiences. It’s the perfect time to bask in the glow of your accomplishments. You know you’ve made a real effort; your sweat and fatigue tell you that.

And there’s nothing like standing around afterward and complaining about a track workout to make you feel like a runner.

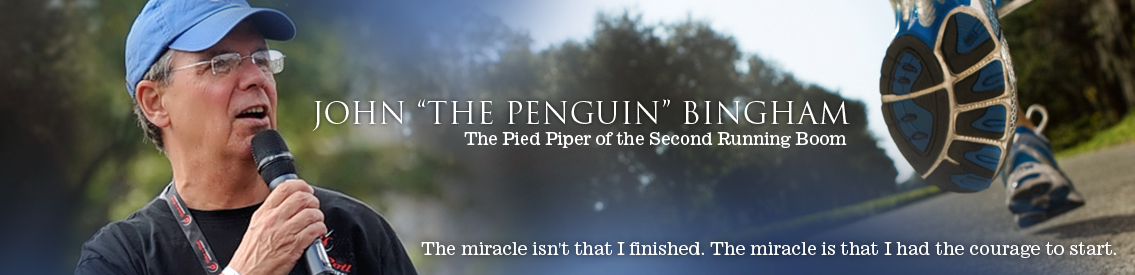

Waddle on, friends.