Getting there is more than half the fun: September 2002

A well-known adage among teachers of musical performance is that the last 10% of improvement takes 90% of the student’s time and effort. This explains why so many musicians reach a point of comfortable mediocrity and then have no desire to go any further. Reaching for those final, tiny improvements is time consuming. It takes equal parts of tenacity and talent.

I’m convinced the same is true for runners. As a beginning runner, I could count on setting a personal record almost every time I raced and adding more miles to every weekly long run. I could rely on my training to produce dramatic improvement. Getting faster every day was a given and going farther every week was my right of passage.

It helped that I was so slow to begin with. Being really out of shape when you start running means improvement occurs in quantum leaps. Taking fifteen minutes off your 5K best requires having run way off the pace charts in your previous 5K. And adding distance doesn’t mean adding miles. When your first long run is less than 100 yards, improvement is measured in feet!

Being naive, I expected my training improvement curve to continue unabated. I calculated that at my beginning rate of improvement, I’d be competitive in about six months, winning age group awards in a year, and would hold the world’s records for my age group at every distance in around two years.

Of course, I got about as good as I was going to get in about three years. I reached what might, euphemistically, be called my potential in less time than it takes to graduate from high school. It wasn’t that there was no room for improvement. It was that I couldn’t justify the price for that improvement in terms of training time and effort. I could have gotten a little faster or gone a little farther, but the risks and the rewards didn’t add up.

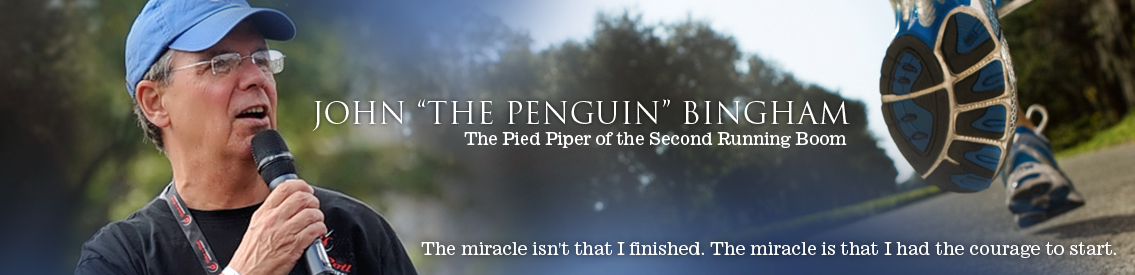

The truth of this was brought home to me recently during the question and answer period after a clinic I was giving. I explained that I’d been running for over ten years and was enjoying it more than ever. One woman asked incredulously “But didn’t you EVER get any faster?” The unspoken question was how could I possibly enjoy something that I clearly wasn’t good at??

Yes, I answered, I did get faster-at least faster than when I started, faster than I used to be, faster than whatever slow once had been for me. But, no, I never got faster in any absolute terms.

My answer didn’t satisfy her. She shook her head, not understanding how I could be satisfied with what most would describe as abject mediocrity in a sport that celebrated velocity. I tried to explain that outright speed had never been the only goal for me. I tried to explain that it was everything else about being a runner that satisfied me, not just speed. She remained unconvinced.

She’s not alone. But, then, neither am I. And I think the sport has room for both of us. I think the sport has room for those who reach their 90% and are content, and for those for whom the pursuit of the final 10% is all that matters. I think there is something lost and something gained in both approaches.

As for me….I’ll take my 90% and be happy. After thirty years as a musician, most of which were spent searching for the elusive 10% solution, I’m prepared to finish my running career just about exactly where I started-very glad to be out there running.

Waddle on, friends.